Jonathan Brookins rested his head back and slowly dipped the tips of his blond dreadlocks in the water, hoping to ease some of his self-righteous anger. This wasn’t the way he’d imagined it, that’s for sure. It was early March, and two weeks ago he’d made minor headlines when he abruptly gave up a promising fighting career and fled to India. He landed on the shores of India’s richest state, a small southwestern region called Goa, with the idea of completing a four-week yoga teacher training course. Brookins had long grown disenchanted with the fight game, but the virtues of meditation and self-introspection had always intrigued him.

This, however, wasn’t what he was looking for. Two weeks into the course, Brookins felt more like he was slogging through high school than on any sort of journey to enlightenment. From 6:30 in the morning to 6:30 at night, with a few short breaks between, Brookins and his many classmates studied manuals, practiced basic yoga positions, and generally learned things he could’ve learned back in the States, all under the tutelage of a western instructor who, by all accounts, was living pretty large for someone who preached the values of humility on the daily.

Brookins felt more like he was slogging through high school than on any sort of journey to enlightenment.

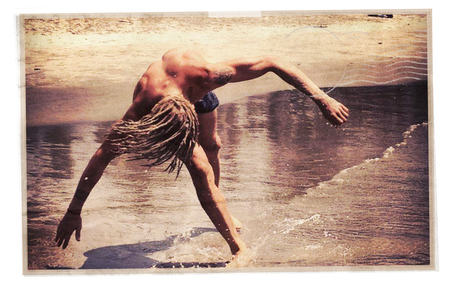

So Brookins laid there, bobbing up and down in the ocean, 27 years old in a foreign land, brooding; veering hard to the left just like he’d always done when things got too structured over on the right. He stared over the edge of the horizon, focusing his gaze where the blue waters vanished into a milky sky, and for a moment he felt the urge to just let the winds and the waves do their business, perhaps tow him to a place where things came as advertised.

But the urge passed. Break was nearly over, and those yoga manuals wouldn’t read themselves. Brookins gradually waded to the shore, awaiting the soft slap of wet sand between his toes. Had he stepped five inches to the right, it would’ve come and he’d have been back to class, another afternoon lost in capitalist yogi hell. Only thing is, he didn’t step five inches to the right.

At first it was sharp, a stabbing thud, like a hammer had crunched all the bones in his left foot. Then it started to spread, intensifying through the lower part of his leg. Brookins yelped, hobbling out from the tide like a suntanned Frankenstein. Hoping for the best, he latched onto the first logical conclusion – those damn jellyfish – but raised his foot anyway to inspect the damage. Much to his surprise, any visible signs were few – just two tiny drops of blood, both of which oozed out from his big toe.

By now the lurching, long-haired American had drawn some attention. A smattering of locals surrounded Brookins to investigate. The moment they saw the trail of crimson dots staining the sand, complete pandemonium ensued.

Brookins recalled an exchange he had with a local a few days earlier. ‘Be careful,’ the man warned him, ‘there are water snakes out there.’ Brookins was more than aware; he’d seen the beasts wriggling to and from the shore on day one. Are they poisonous, he asked. ‘Yes, very.’ Not the answer he’d hoped to hear. Skip forward to his current predicament, as a fervor spread throughout a suddenly gawking crowd, a handful of panic-stricken beggar women rushed over to apply a tourniquet to Brookins’ leg, muttering frantic prayers the entire time, while the man’s words danced through Brookins’ thoughts: ‘Yes, very.’

Blood drained from his face as a realization caught in his throat. “Fuck man, I just got bit by a poisonous snake?! I can’t believe this. I’m going to die.”

Who knows how long Brookins waited. It certainly felt like an eternity, pain heaving up his leg, tremors of anxiety bursting like bombs inside him until help arrived. An ambulance, if you can call it that. Really it was just a battered Jeep with a big wooden board the Indians used as a makeshift stretcher. Brookins’ eyes darted around the inside of the Jeep as it lumbered along the beach and into a thick jungle, the back of his head bouncing off the big board with each bump in the trail. This is what I get, he thought; a foreigner in a foreign land, no cell phone, loaded up in the middle of nowhere with deadly snake venom coursing through my veins.

Forty minutes and another Jeep ride later, Brookins and his entourage finally reached Mapusa. While the city itself smelled strange, the hospital was a different story. Any white-walled sterility Brookins had expected was instead replaced by a washed-out image cut from a World War II textbook. “This was like a bedroom with people in it,” Brookins says flatly.

“The dudes next to me, they’re dying. For real. I’m talking about, you want to imagine people sick, from a culture that’s so far from anything you’ve ever even imagined, and now you’re in their zone of disease that you only hear about in National Geographic shit. I’m right sitting next to these dudes, coughing blood on my pillow behind me.”

Brookins’ head pounded, his left foot throbbed. He’d heard a million stories like this, tourists undone by rookie mistakes, left to anonymous deaths in dim rooms. But those were just stories, after all. Nobody ever thinks it’ll happen to them. Suddenly all that brooding an hour before felt very silly.

AUG. 2012 – FLORIDA, UNITED STATES

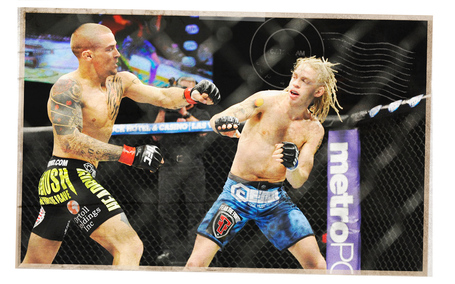

Jonathan Brookins the Man became Jonathan Brookins the UFC Fighter.

Jonathan Brookins can’t remember when he lost himself, just that it must have happened gradually. He was once a couch surfer; a salesman of hope. In a different life, Brookins and his then-girlfriend lived out of a suitcase. They’d walk miles to hang out at the library, simply because the library was free and the dollar wasn’t in surplus. Then somewhere along the way, Jonathan Brookins the Man became Jonathan Brookins the UFC Fighter. After that things weren’t so simple.

Introduced to the world in 2010 by a hypnotizing run on ‘The Ultimate Fighter,’ Brookins presented a curious dichotomy for a testosterone-driven sport. He was the blond-haired pacifist; the spider monkey killer who spoke like he could barely hurt a fly. He’d rip through his competition, then hold his broken opponent close afterward. Celebration meant sitting alone in the backyard of the house, away from prying cameras, quietly practicing yoga; not really knowing what it did, just knowing that it helped soothe his mind.

But the notoriety that comes hand-in-hand with having your dreadlocked mug plastered across Spike TV for 11 weeks straight works in strange ways, and Brookins always took escape in life’s little distractions. The bottle was a frequent companion, as was the occasional psychedelic. So, too, was a swirling mixture of marijuana and tobacco of which Brookins was particularly fond.

He fought most of his early fights high, like the time he lasted 11 minutes with Jose Aldo. He was really high for that one. “I’d smoke it out of a bong,” Brookins says. “Damn near some dudes used to tell me it feels like a hit of Sherman Hemsley, PCP. I was super addicted to it, and it’s a huge rush. It’s a huge, giant spike of this weed, and I based my life around it.”

Most organizations didn’t drug test, or if they did, it was easy to circumvent. Brookins tried to rein it in once the big show came calling, though even that meant stopping his intake about a month before a fight. While he didn’t want to be the guy who had it all and blew his goals over a trivial pursuit, Brookins admits, one month of sobriety wasn’t much.

The chase for fame, though, that was most intoxicating. In early-2012 he stopped Vagner Rocha in just 92 seconds, seizing his first UFC victory in devastating fashion. The ensuing euphoria was dizzying. “I’m doing backflips and celebrating,” Brookins says. “I remember just being so mad at myself. ‘Why did you do that? That’s not you.’ That celebration felt like a mockery of who I was.”

By then lights had melted away the sense of self Brookins once took pride in, first distorting it, then replacing it with an empty pit, a yearning deep inside him which slowly tugged apart his insides – though he had yet to realize it. He lived flippantly, deserting his spirituality and indulging in financial excess. Before the first autumn leaves of 2012 tumbled to the dirt, TUF champion Jonathan Brookins was homeless; a dead broke loser of two of three fights, sleeping on the couch of a friend he hadn’t seen in eight years.

“I was really scared,” he says. “And I didn’t really notice it. You can’t tell because you wear this mask so well. You’re just around all these other dudes who are scared too, but they wear the same mask all the time. They’re training to cover up that mask even more. I don’t know what happened to my life that I was making these decisions.

“I just spent all my money. I spent every dime I had on the stupidest stuff, and I couldn’t even tell you where it went. My car got repossessed because I didn’t have the money, then I just couldn’t afford the house anymore. Once I lost the house, I just lost everything in it, everything I had built. I had a dog there, this whole life. And you keep losing fights, the money keeps flying out the window. I don’t know what to do. It all just kind of crumbled, man.”

DEC. 2012 – TUF 16 FINALE – NEVADA, UNITED STATES

It’s funny, the way the world sends us little signals. On Dec. 13, 2012, Jonathan Brookins’ ill-prepared body gave out inside a hot yoga studio, his grand escape plan nearly dashed by a torturous weight cut. Really, he should have seen it coming. By this time, he wasn’t a fighter in any real respect. That worm turned around the day he begged UFC matchmaker Sean Shelby for another fight from his friend’s couch, which conveniently doubled as Brookins’ bed.

The disorienting stress of poverty and a life increasingly detached left Brookins little choice.

Of course, Brookins didn’t want to fight. His diet consisted of cashews and bananas, for God’s sake. He just needed the money and it’s the only way he knew how to get it. Shelby had thrown Brookins a bone and offered him Dustin Poirier, a hungry up-and-comer who needed a bounce back fight from a failed No. 1 contender bid. It was well beyond Brookins’ rank, and Shelby urged that the offer was anything but mandatory. But the disorienting stress of poverty and a life increasingly detached left Brookins little choice.

Although he had two months to prepare for his last-ditch effort, it may as well have been two days. Any sense of ambition had long since vanished into the bowels of that crusty couch, and the extra time did little good. Brookins wandered from Oregon to New York to Montreal, barely going through the motions.

It was freeing, in the most miserable sense of the word. Brookins had reached a bottom, a place he’d unconsciously been waiting for where this charade no longer seemed sensible. The hole inside him had grown far larger and he’d lost touch. The people around Brookins understood when he told them. I’m leaving for India. No semblance of detail. Hardly anyone questioned it. He was the guy who didn’t even carry a cell phone; something like this seemed like a foregone conclusion. He just needed the money.

So here he was, 24 hours after he talked his way out of a trip to the emergency room for dehydration, standing anything but tall in his underwear in a cramped amphitheater in Las Vegas, drawn out and 146 pounds on the nose. He gazed up at the big screen and marveled at how awful he looked.

Certainly Poirier, with his thinly chiseled physique and determined grimace, appeared much more the part. He, too, hit the 146-pound featherweight limit, albeit much more impressively, then marched to within inches of Brookins. As Brookins nodded his head in acknowledgement and extended his hand, Poirier leaned forward and whispered something in his ear. It wasn’t the usual pre-fight bombast, just a simple statement.

“I want this more than you.”

Brookins smiled wryly, but only because he was so taken aback. Somehow a throwaway declaration, a cliché from a stranger, was the most honest truth he’d heard in months. “It was a slap in the face, in a good kind of way,” he says. “A wake-up call. It was just weird. Maybe you can call it a gift, but at the time I didn’t really think it was a gift as much as it was a realization.

“He believed it. These dudes, man. I just remember thinking, wow, that’s a true statement. I couldn’t say that right now and stand behind my words. I could lie and say I want it, but did I put in the work? I could tell when he said it, he had enough backing behind it. I’ve done this. I put in the work and I’m here. From my angle it’s like, fuck man, do I even want this? What did I do to be here right now?”

He was in the air, on a flight to a place he’d never been, to escape the cycle and find the missing piece.

Brookins lost to Poirier the next day. It only lasted four minutes, but he surprised himself by putting up a good fight. When he got back to Florida, he smoked a bowl, collected his small loser’s check, then began to prepare. A few months later he threw a few old clothes in a suitcase, dropped $2,000 on a plane ticket, and just like that he was in the air, on a flight to a place he’d never been, to escape the cycle and find the missing piece that could pry open his life. It wasn’t hard, even if he was a little scared. Other than personal relationships, he wouldn’t be leaving behind much.

Brookins departed to New York, then hopped over the Pacific Ocean. Counting layovers, it was nearly a 24-hour trip. And he took full advantage of India’s instant hospitality. “I just got super drunk,” Brookins says. “It was weird. I knew I was going over to, in a sense, detox. Seriously detox. But I didn’t even know. I couldn’t guess what was going to happen. My habits – my old habits – were still there pretty heavy.”

Free in-flight alcohol led to a blur of cheap Sutter Home merlot and grayed-out flashes. In a way, it was exhilarating. The glistening blue of the ocean would catch rays of sunlight just right, and down would go another guzzle. It was pitch black, nearly 1 a.m. when Brookins finally landed in Goa, India. He stumbled through the darkness to his rented beachside bungalow and wasted little time ordering another glass of his burgundy poison. Brookins gazed around at the crashing waves, marveling in a daze; his decision validated. It was paradise.

Drunk off wine and adrenaline, he ordered a small meal, which caught the attention of a stray dog. It cautiously poked its nose around the side of the bar, black, medium-sized with the build of a collie, but its paws were wrapped in little shocks of white fur, as if it were wearing socks. Brookins gladly shared his meal with the timid creature, and the bizarre elation of the moment lasted throughout the night, just two strangers in a strange land, taking it all in.

The next morning, however, was a different a story. Brookins awoke, his foggy euphoria gone, replaced by a dark red rash which splashed across his body; overdosed from drunken Indian sun while the wine played cruel tricks on his guts. It was too familiar. He’d fled the west to escape this queasy feeling, to remove himself from his own constant barrage of distractions, yet even here, the distractions followed. No longer would he let them.

Brookins gazed downward with a thick groan, and to his surprise found his friend from the night before still nestled by his feet, chest rising and falling in rhythmic rasps, little white socks curled up under a skinny black body. For a brief moment he was back in Florida, a house, a job, a dog – life figured out, the oblivious suburbanite eternally waiting for the weekend. But the memory was a lie, and somehow that gave him comfort.

Brookins groggily rubbed his eyes, vowing himself, for the first time in a long time, to sobriety. If he was going to get anything out of this, it had to be with a clear mind, and it had to start now. No more excuses.

Beneath him the stray stretched a deep stretch, wrapping it’s white paws around Brookins’ foot. He smiled and named it Mittens.

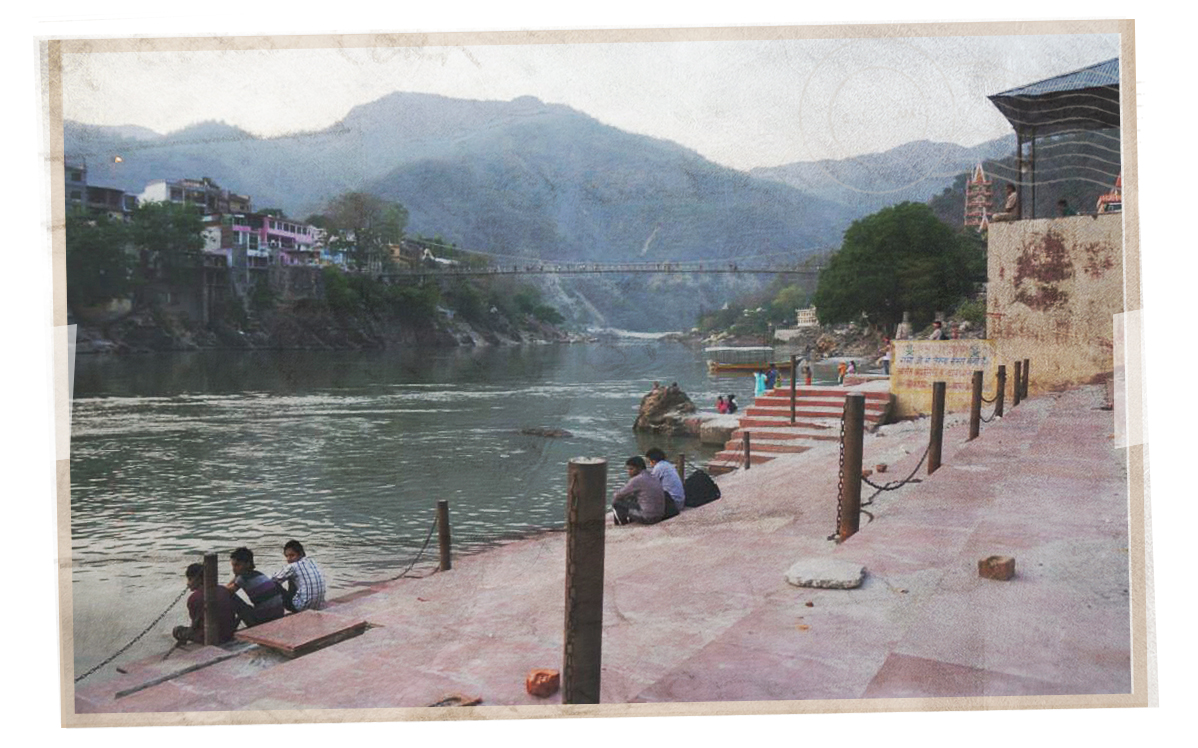

APRIL 2013 – RISHIKESH, INDIA

The sun cast its rays a with heavy sigh over the shimmering surface of the Ganges River. India’s holiest body of water smelled faintly like burning flesh, but located at the foothills of the Himalayas, it provided a welcome sense of cleanliness, which the progressively scruffier Jonathan Brookins had dearly missed during his one-month stay in Goa.

Goa had been interesting enough. The snake incident certainly caused a minor stir, even if it ended up being the world’s most unpleasant false alarm. Turns out not every water snake is fatally poisonous, which is probably a good thing, Brookins thought to himself, though heavily exaggerated stories about the westerner who nearly lost his foot were all the rage around town for a few days.

The real value of Brookins’ stay came from his fellow classmates.

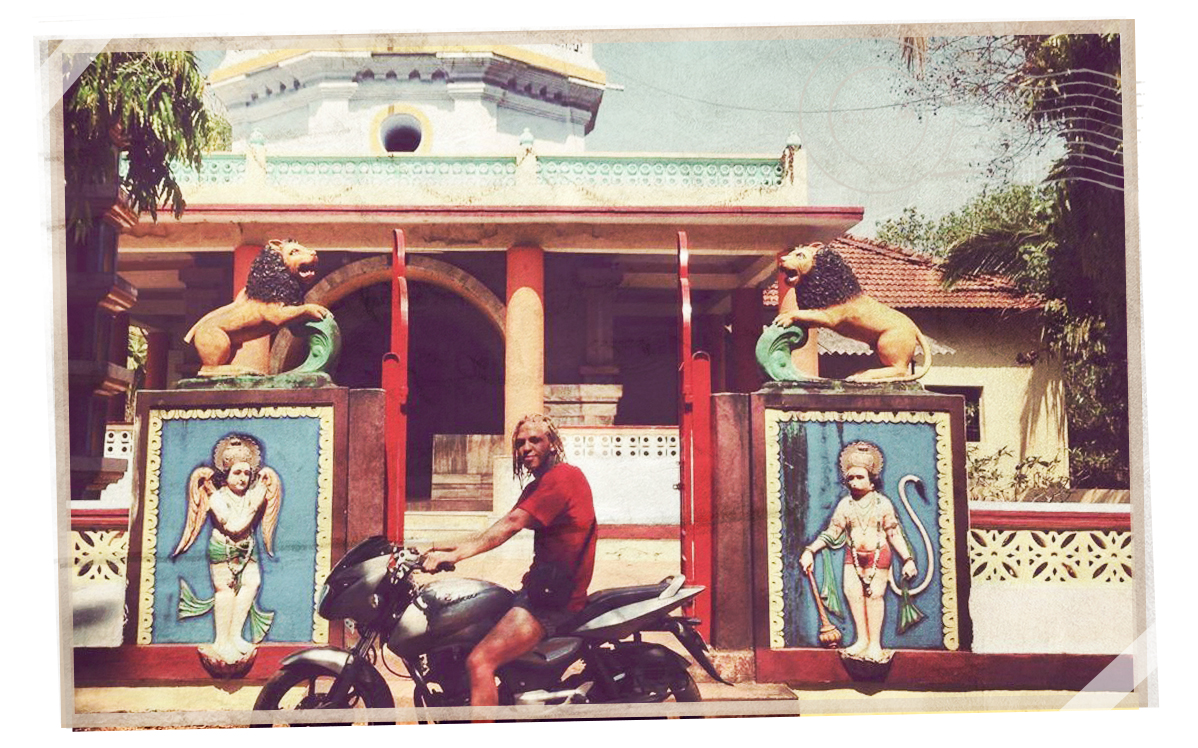

As for the reason Brookins started his journey in Goa in the first place – his four-week introductory yoga teacher training course – that still smelled a bit too much like western capitalist exploitation for Brookins’ liking. Aside from the certificate he got for completing the course, a slip of paper which branded him an official yoga instructor, the real value of Brookins’ stay came from his fellow classmates, an eccentric mish-mash of white-collar clerks and spiritual chasers from distant lands. There was Steggs, a brutish rugby player turned teacher from Australia. While the nickname wasn’t much, he was a nice enough fellow. Then there were Anyu and Hanan, two girls from the Maldive Islands with whom Brookins grew particularly close. The three would rent Royal Enfield motorcycles and explore on their free days, riding up the sandy coasts and back again. But the most influential among them was Bojita.

A 6’4 bear of a man from the Czech Republic, Bojita and his athletic abilities did not inspire confidence upon first glance. Wrapped in a big beard that hid his middle-aged features, Bojita looked like someone who should play basketball, but probably wouldn’t be coordinated enough to do so with any measure of success. Brookins, meanwhile, was an athlete, and when he sized up his competition on day one of class, the big Czech with a proclivity for plucking guitar strings barely registered on his radar. Though that quickly changed.

Bojita turned out to be the picture of yoga perfection, implausibly outdueling Brookins despite his ungainly frame. He was flexible to the point of absurdity and a master of an ancient yoga system called Ashtanga, of which he introduced Brookins. “This dude was flawless. He’s getting on one leg, he’s pulling the other leg up in the air. He ain’t moving. Everything was just focused,” Brookins says.

“This guy was just fully immersed in it. He had it down to where I could see how it worked. If this system could work for this guy, he could be this skilled, this calm, this flexible, and it all came from this system, that’s when I really started to believe in it.”

Initially Brookins arrived in India with the goal of becoming a certified yoga instructor, but without any sense of where to go next. Throughout his month in Goa he played with the idea of traveling on a whim, ambling south in some winding direction and seeing what came of it. But once Bojita and Ashtanga left their imprint in his head, Brookins knew his next target. He caught a flight to Delhi, then took a seven-hour ride up north to Rishikesh, the home to the Ganges River, and a city often referred to as the yoga capital of the world.

The nickname wasn’t a lie. Brookins disembarked into a veritable yoga supermarket, where a smattering of fliers promoting different shalas (yoga studios) could be found on every street corner. With an eye on Ashtanga, Brookins tested out a few instructors until meeting a yogi by the name Kamal Singh. Kamal was a spry, gaunt-faced teacher, uncannily wise with a cascade of long, dark hair that fell to his shoulders. He founded the shala Tattvaa, and the moment Brookins walked in to see a perfectly synchronized class ebbing and flowing without any brash instructor barking out commands, he immediately felt at home.

His initial culture shock had faded; the time had come for Brookins to make good on his trip.

His initial culture shock had faded; the time had come for Brookins to make good on his trip. He rented nearby housing for a meager 200 rupees a night – a little more than $3 a day – packaged up his old American clothes, mailed them home, and thrust himself into a lucid immersion into Indian spiritual culture. “I really started to let go of my life as a fighter,” he recalls. “I started to contemplate what life would be like without it.”

Between daily trips to Tattvaa, Brookins dialed back his diet to a steady stream of fruit from local fruit stands, fresh yellow bananas and juice-filled mangos, and began experimenting with his body. He’d fast for upwards of six days straight, slowly roaming the cityside clad in traditional Indian garb, a tousled wanderer with an odd, mellow fatigue tugging at his impulses. “A lack of real strength,” Brookins calls it.

“I would play around with that feeling, and then I would do the yoga, and it would instill this type of energy to me, from the lack of food. That’s when some of this stuff started to click. Wait a second, there’s something to this, because I am feeling better. I do actually feel strong. Somehow I’m getting energy from this.”

His studies often led him to the banks of the Ganges, a river where tradition melted faintly out of the cool, serene air, and Brookins would close his eyes and attempt to bury deep within himself. It’s there that he met Swani.

MAY 2013 – RISHIKESH, INDIA

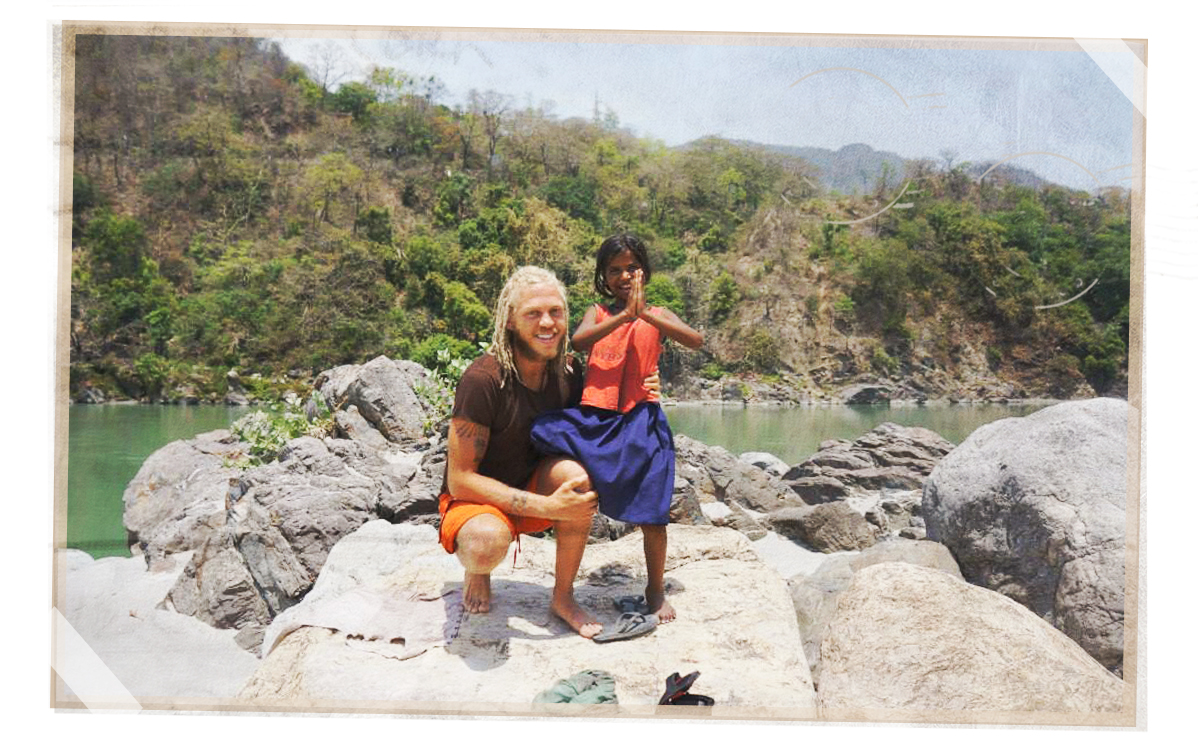

Everything started innocuously enough. A soft cry broke Brookins from his meditative haze. He turned, surprised to find a little girl no older than 7, long black hair tucked behind her tiny ears. She had a sixth sense about the rupees that lined Brookins’ pockets, and though her frayed American T-shirt gave off a disheveled look, she couldn’t have been more adorable.

India is a massive country, the second-most populous in the world. More than a sixth of the world’s population lives within its borders, and an unsettling percentage of that population lives below the poverty line. Begging is common, particularly among children, and Brookins was always one to have a problem saying no. Almost half of his money was begged out of him over the course of his time in Rishikesh. More than once he had serious giver’s remorse.

“Who am I to deprive them of the same wants and desires that I had as a kid?”

“My situation isn’t much different than that person’s, other than the fact that they were born in India and I was born here,” Brookins reasons about the U.S. “When these little kids are asking things of me, who am I to deprive them of the same wants and desires that I had as a kid?”

So it was like taking candy from a baby when Swani and her friends bumrushed Brookins, politely requesting 500 rupees to buy a dress for school. Brookins half-heartedly obliged, then shooed the delighted children away. But two days later they were back, and thoroughly excited to see him. The group asked for more money. They said it’d help fund their school tuition, of which they couldn’t afford on their own. Considering the fact that he just bought a dress for an apparently nonexistent school, this time Brookins wasn’t in the mood to get hustled by a gang of street kids, so he asked for proof.

“Sure enough, they took me to their school,” Brookins says. “It was this really great place. All these other kids were in uniform, hanging out and playing. It’s like, ‘Damn, you guys need to be doing that.'” Brookins spoke to the school’s principal, a gruff man who didn’t seemed thrilled at the prospect of beggars joining his ranks. Nearby patrolmen scolded Brookins, ‘These kids are bad kids. Leave them alone.’ Still, he learned what he needed to know. Tuition for each child was only $8 a year, but that $8 didn’t include books, clothes or supplies, which were significantly costlier – the main hurdle for kids without financial means.

The next morning Brookins met the group of children by a large bridge on the banks of the Ganges River. Four were expected to show up, but word apparently spread and six stood before him; two boys, four girls, ages 7 to 12, all with a dim glimmer of hope in their eyes. And so they set out; Swani, the youngest of the three girls, alongside Shoba and Rahda, with little Krishna bustling in back with his two buddies.

The whirlwind of shopping that followed almost felt like a dream. “These kids had the best day ever,” Brookins laughs as he remembers. “They got fully decked out in school supplies and clothes. They got to go eat. It felt like I was taking kids to Chuck E. Cheese.”

“I can do so much more with the money I made from fighting than I ever could’ve even imagined.”

In the end, it cost Brookins almost nothing. Just $250, and all six were loaded up with all the gear, books and tuition they’d need for the upcoming year. The party giggled and played around him, any unjust truths of their lives swept away if only for a day, yet the patrolmen’s harsh words still rattled around inside Brookins’ head. These kids are bad kids. “They’re not bad,” Brookins says after a pause. “They just don’t have a chance.

“Sure, some of the kids you could tell, they were just trying to get one over. After they got stuff and they were done with you for the day, some of them would just split. No thank you, no nothing. But my instinct for Swani was perfect. She would wait after, and every time just say, thank you, thank you, a thousand times thank you. She was really appreciative. Even if it’s just one out of the six that sticks, if it gives her the understanding that people are kind, good things can happen if you believe, and her life does something, it’s worth it that way.”

Brookins’ voice warms as the memory leaves his thoughts. “That was really life-changing for me, in a sense. ‘Wow, I can do so much more with the money I made from fighting than I ever could’ve even imagined.'”

JUNE 2013 – DHARAMSALA, INDIA

Sunlight poured through streaks of a smudged window as the bus lurched to a careful stop. Jonathan Brookins yawned, raising his arms high above his head, a crude attempt to ease 14 hours worth of lactic acid build-up, then peeled himself off his seat to shamble toward the front. For however janky it’d looked on the outside, the overnight bus ride had been a good idea, he decided. A daylong road trip is much easier to stomach when you sleep through half of it.

He turned his gaze up, only to be greeted by one of the most beautiful sights he’d ever laid eyes upon.

Brookins barely reached the bottom step before the fresh mountain breeze socked him right in the face. The feeling was all too welcome. He turned his gaze up, swallowing deep mouthfuls of the cool air, only to be greeted by one of the most beautiful sights he’d ever laid eyes upon. Strings of colored flags dotted the skies while dense bunches of lush green cedar trees mushroomed across the horizon. Ornate rectangular buildings of differing shapes and sizes poked upward through the mountainside, and above all else, that odd urban smell was nowhere to be found.

Dharamsala was an easy choice, and, it seemed, the right one for Brookins’ last stop. His two months studying under Kamal Singh in Rishikesh had been eye-opening, without question. If Goa had first taught Brookins a lesson in how to treat others, then Rishikesh had given him a crash course in how to treat himself. But now the warm months were over, and the hot months were wreaking havoc on the countryside – including Brookins’ non-air conditioned Rishikesh guest room.

It’d only cost him 200 rupees a night, so it was hard to complain. The room sat at the very top of a guest house, where it’d bake in the scorching Indian sun all afternoon while he busied himself with his studies. His last few days in dusty Rishikesh, Brookins had laid wide awake at night, broiling inside a 107-degree microwave, drenched in sweat like he was cutting weight. It’d only made sense to move north, and Brookins already had a target in mind.

He’d first heard about Dharamsala from Inga, a classmate of his during the four-week teacher training course in Goa. She was a young woman from Switzerland whose spirit radiated positivity, and she caught Brookins’ ears with her stories of vipassana, a grueling Buddhist trial of restraint and self-introspection. Practitioners of a vipassana abandon their voice to enter into 10 consecutive days of silence and deep meditation. For 10 hours a day, spiritual seekers from across the world sat cross-legged on the floor of a meditation hall, eyes closed, unmoving and unspeaking, barred from any semblance of eye contact. Inga had undergone two vipassana, and her words left Brookins curious.

“Some days it feels like bombs go off, kind of explode within you.”

“People explain it as, some days it feels like bombs go off, kind of explode within you,” he says. “[She] explained it more like chiseling. It felt like there was concrete layers in my brain and each day it was chiseling away these hard layers that’d crusted over. After hearing those types of testimonials, I was like, ‘I’ve got to try this.'”

Vipassana seemed like a logical next step in his studies, and by now Brookins was ready. The most renowned vipassana was in Dharamsala, a Tibetan exile settlement built high up in the Himalayas, home to the Dalai Lama. And so there Brookins was, gulping down swigs of cool mountain air as he tugged on his blond whiskers, staring out at the natural green splendor that stretched as far as the eye could see. It almost seemed to envelop him.

Though perhaps it was too much, since it took a full month before Brookins drove up the will – and, in a way, the guilt – to give himself up to the 10-day journey. The mountainside was intoxicating, starting with the eggs and toast he’d wolfed down first thing after the bus ride. It’d been the first real meal Brookins had eaten in months, and many more quickly followed. Cafés lined the town’s streets, each one quaint, but strangely majestic, eastern Asian architecture rising from the highlands. Brookins gorged through all of them as he resumed his training, first a two-week course on Iyengar yoga, then a similar course on Tantra yoga to keep himself busy.

He made friends with locals and travelers alike, yet each week the specter of vipassana tugged at him. That hole inside Brookins may have been smaller, but it was still there. He knew it. For a time he’d mentally talk himself out of it at the last minute. Why shut myself off for 10 days when I could be out here eating pizza? But by the end of the month, the indulgences of Dharamsala had packed nearly 15 pounds onto Brookins’ swollen frame. Enough was enough.

JULY 2013 – DHARAMSALA, INDIA

Nearly 100 people surrendered their voices at the front door.

The first day was easy. In an odd way, it almost felt like a miniature college campus, only instead of registering for class, nearly 100 people surrendered their voices at the front door. Meditators were separated by gender, about 50 men and 50 women, each person here for their own reasons, and shown to their dorms. The phrase “dorms,” though, only worked in the loosest sense of the word, since each room was really just a small square of space separated from the next by what looked to be a thin shower curtain. A rough wooden slab jutted out from the floor, with a few towels thrown on top to make up a crude Home Depot project of a bed, but it would have to do.

Brookins awoke on day one at 4:30 a.m., groggy and silent, and hiked to his first meditation session, avoiding eye contact with passersby. The lack of awkward small talk was already a nice change of pace. He soon found himself standing outside the threshold of a big Gompa (meditation hall), gazing into a gridlock of pillows on a thickly carpeted floor. Décor was sparse, yet the room seemed strangely beautiful. Each section was labeled, Brookins noticed as he slowly ambled along the rows until he found pillow pile D5, his home for the next 10 days.

The hall was fairly dark, not pitch black, but dim enough so that reading would be a challenge. Brookins lowered himself cross-legged onto his bottom pillow, which was thick like a couch cushion, and propped himself up with his smaller secondary pillow. Others sleepily filed in around him, men on one side, women on the other, while two elderly figures, one man and one woman, sat quietly, motionless at the front of their respective section. Brookins studied the old man intently; bushy mustache and a curious glass eyepiece. He reminded Brookins of an Indian version of a guy he’d seen on a cereal box, though he couldn’t quite place where.

Their directions were simple. Just observe your breath. It was a vague start, to be sure, but it kept Brookins busy enough for the first two hours. Amidst the silence his mind would wander away to thoughts of his journey, questions about the UFC and back home, until he’d catch himself, his eyes snapping open after five or so minutes lost in deep thought, and he’d redirect his focus toward the gentle inhale, exhale of his body at work.

So it went for the rest of the day. Breakfast was at 6:30 a.m., then it was back to the Gompa for three more hours. Lunch break came at 11:30 a.m., followed by another four-hour session until 6 p.m. From 7 to 8 p.m. came discourse, where the group would gather around the Gompa and silently watch a video, delving into Buddhist philosophy and recapping the day’s experience, until one last hour of meditation wrapped up the night at 9 p.m.

By day six, Brookins wanted to die.

If day one was easy, day two was repetitive. By day six, Brookins wanted to die.

Minutes stretched into eternity, crawling along at a snail’s pace. Brookins slowly burned holes through his eyelids, hour after hour, second after second, staring into darkness in that crowded Gompa.

Sleep was a myth. The wooden slab of a bed was unforgiving on Brookins’ aches, while his neighbor’s foghorn snores cut through the night. It was amazing, in a macabre way, the sounds that came from the other side of that shower curtain. Brookins first stuffed toilet paper in his ears to dull the roar, yet even when he managed to drift into a weak doze, he’d still find himself screaming at the figments in his dreams. I can’t hear you! It’s too loud!

The sleep deprivation began to play tricks on his thoughts, and life inside the hall wasn’t any better. Brookins realized quickly, his western body, still engorged on the treats of Dharamsala, wasn’t designed for this task. “You’re not just chilling,” he says. “Your back isn’t on a chair. You’re on the ground, holding your body up straight. As the pain and all these things started to set in, and the back starts to get sore, you have to combat that.

“Your brain really starts to struggle with the experience that it’s in. ‘I’m not used to this.’ It starts to really revolt.”

The constant barrage of discomfort began to drain him, as well as those around him. Others snapped, abruptly standing and shuffling out of the Gompa, quitters as early as day two. Brookins envied them. Ten days seems like an eternity when one hour lasts forever. At times Brookins couldn’t help but clench his eyes shut in impatience, unable to sit another minute in that silent hall. He might as well have willed himself off the planet.

Yet something else was changing, too. After three days spent trying to observe his own breath, Brookins gradually became aware of odd subtle sensations he’d never felt before. All the outside stimulus, the distractions of daily life, were gone. The tingling on his lip, that was far realer. As the days wore on, he began to understand the sensations more. Brookins’ body swirled in a constant in a state of flux, and for once he focused on the interior, not the exterior. The lessons of the previous half-year began to take shape.

By the fifth day Brookins had become more flexible. By the sixth, the pain in his knees and back were a distant memory. Weight melted off his frame and the stresses of the world blurred. By day seven, Brookins could bury deep inside of himself for an hour without breaking focus. He began to grasp the results, the culmination of months of studies, and it was inspiring. “To me, it didn’t feel like an hour. It didn’t feel like anything,” he says. “It felt like I was actually involved in something that took my mind completely off of time.

“I’d be inside, but it’d be like I was watching an entertaining movie. One you enjoy, that you could watch for an hour. An hour passes and you don’t notice the [passing] of an hour. You’re not checking the time. When I could get there, that’s when it started to get fun.”

After that first meditative hour, the last few days flew by. By the time Brookins reclaimed his voice on day 10, he felt more in the moment than any time previously before in his life. “They say it takes 21 days to acquire a new habit,” he says. “For those 10 days, you’re starting to etch out a new neuro-pathway for your brain. That’s most definite. It’s a different neuro-pathway than you’ve ever used before. You’re used to so many things as humans; speaking, etc.

“Everything that I am today, it was all thought up and created inside that little Gompa.”

“This day and age, we don’t know ourselves. Not truly. We’re just products of a freaking algorithm. We’re so learned from everything that everybody else has done, but we never sit and observe our actual sensations. What does it feel like to want or to crave? And do I have to give into that?

“Everything that I am today, it was all thought up and created inside that little Gompa,” Brookins continues. “It wasn’t an immediate feeling. I wish I could’ve known that. I wish I could’ve looked back and known that, but I did kind of feel it. Nothing changed at all in those 10 days, other than the fact that I left with a tool. I was chiseling away at these concrete layers on my brain, and it felt like when I left, the only thing they did was let me leave with that chisel and hammer.

“That was unreal. And now I can still chisel away any time I want. I can do anything I want now. I have the tool now to actually be in control of my own mind. The tool to combat negative behavior.”

NOV. 2013 – MONTREAL, CANADA

Jonathan Brookins leans forward inside his dorm at Tristar Gym and fiddles with the touchscreen on his iPad. His scratchy blond beard, the result of nine months without touching a razor, is quite impressive by now. He’s been back in North America for a few months – his visa expired in late-August, the Poirier money was getting tight, but most of all, it was just time. Though only in recent weeks did Brookins make his way back to Montreal. For the most part, the transition is going smoothly. “And that’s the part that feels most surreal,” he marvels. “It’s almost exactly how I imagined it.”

“I’m the competition. This whole fighting thing is about your internal battle.”

In a weird way, this almost feels like college all over again; a chance for Brookins to get his four-year degree at Tristar University. Fighters shuffle in and out of closed doorways during breaks in the daily training schedule. Laughter echoes throughout conjoined dorms. The camaraderie is palpable. A few days after he arrived, for the first time in a long time, Brookins sparred with his old teammates. It was obvious pretty quickly who’d been training and who spent half a year trekking across India, but even still, the experience awoke a different sensation than it used to.

“I call it a fighting spirit, but not fighting somebody else,” Brookins says. “And I always kind of knew that – these other people weren’t the competition. I’m the competition. This whole fighting thing is about your internal battle. You’re making yourself better through this. It’s not getting yourself prepared to fight somebody. You’re just using this tool to make yourself better.

“All this money, fame, this, that and the other,” he continues. “Truly in your heart and soul, you get to this place at 60, and you have some fond memories, but truthfully you’re unfulfilled and unhappy. You have that feeling, and you can’t shake it. ‘What is that? You tell me.’ That’s scary, and a lot of people get there. They get to a certain place and they have lots of things. Lots of good, fond memories – pictures in a book. But something is still unfulfilled, unhappy. That’s the conundrum, and it’ll happen to anybody.”

Brookins isn’t retired, although he wrestled with the idea at first. It wasn’t indecision. That indicates a hesitancy that didn’t actually exist. He simply struggled with a question – how can one live a life spent running across the entire world, learning how to separate oneself from pride and ego, then compete in a sport that’s dominated by those very two things? “That’s the riddle,” Brookins admits. “The thing is equanimity. I’m realizing, that’s the root of my life right now.

“I had truths when I got out of ‘The Ultimate Fighter.’ I had people who had my back. I had a girlfriend, that type of thing. But I didn’t want those things anymore. I wanted something else. I was searching for something else. It drove me crazy. But I didn’t have this understanding of truths that really are. That’s going to be a key factor. I have these truths now that are so strong.”

A week ago Brookins returned from his second vipassana. It was close by, and any nerves that may have existed back in July were long gone. This time around, the experience validated what he already knew.

For now, Brookins is back to being a fighter. He’s the lightest of his career, and he’s rededicated himself to a new start at bantamweight. “I’m dead set on it,” he vows. “I’ve got to get back there. I don’t see anything else but a championship. I know I can manifest it now. I know I can. I have the mind now to do anything I want. Anything. If I really wanted to get into the NBA by the time I was 40 right now, it would probably take me to that time, but I could probably do it. Somehow, some way. That’s the way I see it for fighting.”

He’s still sober, too. That’s one part of which Brookins is particularly proud. And that teacher training certificate from Goa? He put it to good use. Everyday at 9:30 a.m., without fail, Brookins is smack in the middle of Tristar’s new hot yoga room, quietly focused, intent on practicing his craft. Some days nobody comes. Some days, though, others join him; newbies simply looking for guidance, or old beaten bodies shuffling in, grasping for any semblance of relief. Brookins enjoys those days the most.

“This is the first time in my life I even understand what happiness is.”

“This is the first time in my life I even understand what happiness is,” he says. “It’s nothing ‘The Ultimate Fighter’ could’ve brought me, none of that money, nothing in world could’ve told me what happened until I actually figured out how this world actually works. Now I know what happiness is. You’ve got to really fucking detach. Some people, it doesn’t take that to be happy. But for a guy like me, for some reason, I’m much happier than any time in my whole life.”

If he used to be bitter about his self-sabotaged UFC career, Brookins doesn’t let on. Perhaps he used to feel the stabbing pangs of regret, laying wide awake late at night, wondering what could have been. Those feelings, though, are lost, buried somewhere in Swani’s bookbag, washed away by the Ganges River, left to rot high up in the Himalayas. This isn’t the end of a journey. The hole in Brookins’ stomach, that sense of wandering confusion that used to tug at him day and night, is just a memory now. Goa gave him raw material, Rishikesh shaped it, and Dharamsala forged it. Brookins has his tool. How he uses it from here will be the true author of his story.

“It feels like a perfect plan,” Brookins pauses then smiles. “Like a perfect circle. Now more than ever do I feel like I’m right exactly where I’m supposed to be.”