Scott Smith will forever be known for the Hail Mary he landed while clutching at his liver against Pete Sell back in 2006. The knockout wasn’t a “miracle” in the theological sense, but it was improbable, and it did redirect fate before we even knew whose fate was being decided.

The sequence lasted all of a few seconds.

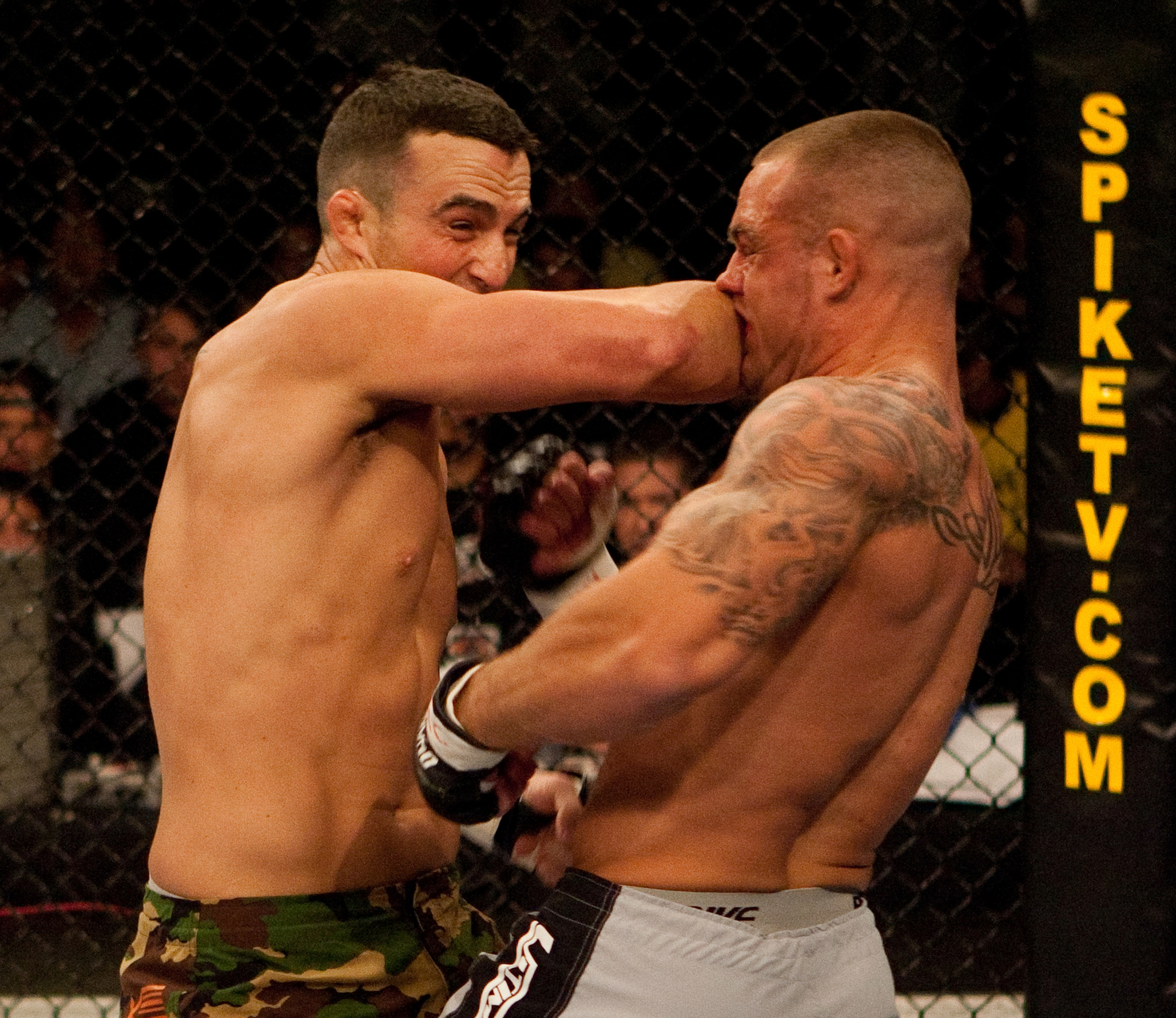

Smith getting caught with a short left to the body…Smith doubled over, rapidly retreating towards some safe haven that didn’t exist while Sell’s nostrils flare to the smell of blood in the water…Smith glancing up, still holding his side with his left hand, as Sell closes in for the finish…Smith planting and erasing the onrushing Sell with his right hand.

The whole thing felt like a cinematic put on. Real life fights just don’t end like that.

Yet it wasn’t fiction that night at the Hard Rock Hotel. It happened at The Ultimate Fighter 4 Finale — the “Comeback” season — and Smith, as if on cue, showcased one of the fight game’s most ridiculous comebacks. People were lining up outside to get their picture taken with the man who snatched victory from the jaws of defeat. Mark DellaGrotte, who was one of Smith’s coaches, had to pull Smith aside afterwards to emphasize the gravity of the moment.

“He said, ‘you need to understand how big this fight will be for your career and the rest of your life,’” Smith says. “It was pre-recorded, so it hadn’t aired on TV yet. To me it was just another fight. It all sunk in a little later when I saw everyone’s reaction, and I was like, wow, guess it was a big deal.”

At that moment, at 26 years old, the owl-eyed fighter who came from a family of steel workers — who, in fact, carried the apt nickname of “Hands of Steel” — hit the high-water mark of his career.

In 2014, that particular comeback feels like a lifetime ago.

“Those were the best times for me because my alcoholism hadn’t really kicked in yet,” Smith says from his hometown of Sacramento, where he is doing another stint of rehab. “I had some really good fights after that, but I think being on the show, that was the best shape I’d ever been in my life. And with the WEC right before, I wasn’t doing it for the money. It was a true passion for me. I think that’s when I was peaking.”

Smith is now 34 years old. As of Sunday, March 30, it has been 41 days since he last took a drink. This is important, because today’s Scott Smith fights himself constantly, hour by hour, day by day, craving by craving. He battles the urge to drink and be done, once and for all, with the endless feat of deprivation. He deals in words terms “triggers” and “pink clouds.” The Comeback Kid is trying to keep going, to keep coming back, to keep fighting, but the lure of the bottle keeps dragging him off.

In fact, he was supposed to fight in early February for the West Coast Fighting Championship, to defend the middleweight belt that he won in August when he competed in the midst of an eight-month run of sobriety, but he fell off the wagon.

“It was eight months and two days that I’d stayed sober, to be exact,” Smith says. “But I kind of f—ed the promoter over, who’s a friend of mine. I was supposed to fight, and thought I’d be ready, but it was one of those, well, next weekend I’ll start. Then okay, next weekend. And then it never happens. I have a lot of amends to make there. I haven’t personally talked to him and I wouldn’t blame him if he didn’t trust me to fight for him again.”

How did Scott Smith end up here?

There was a time when people like Pete Sell and Justin Levens and David Terrell worried about getting taken down by the muay Thai practitioner who just happened to be a wrestler-at-root. In the TUF house, this was a big chunk of the scouting report. He had hands, he had the eight limbs, but he had an ability to dictate where a fight took place and he knew how to grind. Yet as time went on, as he began fighting the Robbie Lawler’s and Benji Radach’s, as he went through his Cung Le days and into the vertigo of the Strikeforce tailspin, he just preferred to stand and trade.

“I got away from the wrestling, to where I only really cared about the muay Thai and the stand-up,” he says.

By the time he was fighting Tarec Saffiedine and Lumumba Sayers at the end, he was essentially an immobile target, an automaton standing still and getting clubbed in the head to the point that people were worried about his well being. It was hard to watch. His chin was diminishing, because his chin was always flashing neon and open for business. Realistically, he’d become a punching bag for people to tee off on — and that’s exactly what everybody was doing.

But what most people didn’t realize was that Smith was already a full-blown alcoholic, who by his own admission would drink “at least a fifth of vodka” after getting his kids in bed, while making their lunches for the next day and doing household things. “A closet drinker,” he says. “To the point that even the people I usually drank with became supportive of me.”

And with each fight camp, he’d drink as long as he feasibly could before getting down to business. Right up until fight week, when Smith would essentially go cold turkey right as he left for the airport. He became a clammy, barely functioning mess just when most fighters are building themselves towards optimum shape.

“You leave Tuesday for a Saturday fight, and I remember my last Strikeforce fight I drank that Sunday night,” he says. “I didn’t sleep that Monday night, Tuesday night or Wednesday night. I was throwing up. I finally got a little bit of sleep Thursday night. I weighed in on Friday. I was a complete wreck, and I had no business fighting.”

Smith lasted only 94 seconds against Sayers in Columbus, getting choked out mercifully in the first round. That was it for Smith in the well-lit theaters.

“You know what’s crazy, though, is when I fought in August [against Mark Matthews], in probably the longest period of sobriety I’d had before ever fighting, it was sort of the opposite,” he says. “It was like a head game to me. I was sort of questioning myself, like, ‘man, can I even do this? Maybe I can only do it when I’m drunk.’

“That was worse than the first fight I ever had in the cage. I kept thinking, you shouldn’t be doing this. Everybody was like, you’ve been in so many battles, he’s never been in the battles that you’ve been in. And I’m thinking, yeah, but this is a different battle. All that means nothing. I was really questioning myself. That’s why I had stage fright going in, to where really I didn’t do anything in that first round. It was a really big mental hurdle. Even there, in the cage, I was thinking maybe there’s something in my head where I need to drink to fight.”

He didn’t though. And he won via TKO in the second round. It was the first fight Smith won since his 2009 upset of Cung Le, the fight that sent him on a delusion course that only now is straightening itself out.

A little while after that triumph, he was drinking again. That’s now 41 days in his rear view mirror as of Sunday, March 30. The fact is, he’s counting.

*

Smith’s second most improbable comeback — in a career that sustained itself on comebacks — happened at Strikeforce Evolution, when he played the role of a melon on a fence post for Cung Le’s assortment of kicks. Smith was dropped in the first round with a spinning kick, and pounded on. He was slapped with a roundhouse kick. There was a spinning heel kick. Le was on a striking spree, just doing demonstrations for an adoring public, and Smith kept dropping. And kept standing back up.

Second round, ditto. Referee “Big” John McCarthy hovered over the action for ten minutes in a ready position to stop the fight. Smith kept standing up, all heart and fumes. Le kept teeing off. Then in the third, after more of the same, Smith, still moving forward, clipped Le with a short left hook. Le was hurt. Then Smith came on, and went for the finish. It was a right hand straight down the boulevard that effectively put Le away. The lid blew off the HP Pavilion in San Jose. Blood streamed down Le’s nose as they shined the flashlight in his pupils.

That fight was prototypical Smith on every level: Perseverance and heart ahead of movement and self-preservation. He won by simply not perishing. And for as glorious as it was at the time, that fight enabled Smith to delude himself to the point of no turning back.

“I was talking about this in class last night, because you try to pinpoint everything in your rehab,” he says. “Five weeks to the day before the Cung Le fight, I was in Chicago doing some Strikeforce commentating, and that was when Fedor Emelianenko was fighting. I was on Inside MMA doing the weigh-ins, and I was told live on television that I was fighting Cung Le five weeks out.

“I wasn’t drunk, but I was actually drinking before I went on the show. I just remember thinking to myself, oh my god, I’m not training, I’m five weeks out and I’m fighting one of the biggest fights of my life. Yet, I did come back, I did get my s–t together for five weeks which isn’t long enough to get ready for Cung Le, and I did get ready for the fight. I got ready for the fight as well as I could in that time, and got lucky and won the fight, and I think maybe my ego took over. I thought, see, I can do this. And then I went straight downhill after that fight. I definitely wasn’t ready for the rematch. I got a big head. I thought, hey, I can drink, I can party, and I can beat Cung Le.”

Le avenged the loss six months later at the same venue in San Jose, this time finishing the job with a spinning kick and a barrage of screaming punches. Smith lasted a little over two minutes against Paul Daley in St. Louis. It was all downhill, and fast. By that point he was fighting strictly for a paycheck, something he’d sworn he’d never do. And he was drunk bell-to-bell, save for the five days or so of fight week matters.

After losing to Saffiedine and Sayers, and looking like a human piñata in both, Smith’s relevance as a fighter was all but over. He still wanted to fight, though. He still had fight left in him. Enough that, after his family intervened and tried to get him help to no avail, he voluntarily checked himself into a detox center in Sacramento in early-2013.

For the next eight months (and two days), he lived in the bewildered state of sobriety, returning to the cage in August for his fight with Matthews. It was a new and foreign way to look at the world. During that time he kept away from triggers, things that would make him want to start drinking. He built his streak day upon day, and was feeling in control.

“In sobriety they call it a ‘pink cloud,’ where you think you’ve got it made, you can have a drink here and there,” he says. “I wasn’t on a pink cloud, but I really thought that there was no way I was ever going to drink again. That’s how confident I was.”

Then the cravings took over. He fell off the wagon late in 2013. And he knew when he did there would be nothing casual or social or manageable about it, but that he’d go right back to where he was.

“Which was drinking in the mornings, drinking all day everyday,” he says. “I did that, and I’ve been kind of battling that for the last three or four months. I couldn’t do it on my own again, so I went back into detox. It’s kind of just a kick in the ass for me.”

That’s where Smith is now, building on his new day-to-day sobriety. The whole thing is cyclical in his chosen field. Among Smith’s many triggers is the act of watching fights.

“I’ve realized it through counseling, that I need to let go of the past,” he says. “I f—ed up a good opportunity, which not completely — I’m not done — but I still dwell on the fact that in my prime I kind of pissed that away with drinking. So, it’s easy for me to drown my blues and drink while watching fights.

“Even a couple of weeks ago, when Robbie Lawler fought Johny Hendricks [at UFC 171]. Lawler is somebody I fought. I was on the same level as him for a little bit. So things like that…people, places, things, I just didn’t want to watch the fight. I was rooting for him, wanting him to win, read it online, but I just rather distance myself from things that might be a trigger.”

Smith says he’s began training again, and that he still feels like he has it in him to fight, perhaps to a potential that he let slip away. At 34 years old, that would seem improbable. Then again, if there’s a fighter who turns improbable on its ear, it’s the Comeback Kid himself. He’s not kidding himself, and he’s very honest about it.

“It’s a daily battle, but this anti-craving med I just started when I went into a detox house a month ago, is helping,” he says. “It’s a non-narcotic, non-benzo, because I don’t like medication at all. So, it’s nothing that would show up on a drug test. It’s actually helping.

“The first couple of days I took it were ridiculous on how bad my cravings were. But I was told, after the fact, that your cravings would get worse before they got better. But it’s very manageable. You can’t control triggers…triggers just show up. My cravings are manageable, to where I’m not thinking about it three hours after the fact. Now it’s triggered, I deal with it, it’s gone.”

Whether it stays gone is the question. That alone will determine what happens next for Smith. Right now he’s trying to feel comfortable in the cage he wakes up in every day more than the cage he competes in. Fighting, in fact, is a dangling carrot he keeps just within reach. It’s a destination as much as a reward.

And right now, on March 30, 2014, it’s all Smith can do to stay towards it, and to keep away from that place where there’s no coming back.